Ode to Chocolate

Our gift to chocolate loving humans everywhere

Sometimes, the puzzle pieces fall into place on their own. In September 2023,

and published a collab titled “An Ode to Coffee.” A chocolate gal can’t not respond to a post like that… coffee and chocolate go together like wine and cheese. Not to mention that the “Ode to Coffee” was published a day after I launched The Cacao Muse (really, there was no plot among the three of us). In our comment thread, Michael said, “We totally do need to weave the two together!!” and Andrew said he’d like that. Then, in December, they wrote “An Ode to Beer.” Those of you who know I come from the Czech Republic might think I’m a staunch fan of my country’s famous beer—yet I drink neither coffee nor beer. Still, it seemed to me that the Ode to Chocolate needed to be written, to complete the Trinity, as it were… and a month or two later we decided we would do it.And what more special day to publish an ode to the world’s most beloved food, than on the day that celebrates some of the most special people in our lives… our mothers. This is a gift to all the mamas everywhere, and all the chocolate-loving humans they have brought into this world.

Darkness descended on the ancient village, closing the last bit of daylight off from the room inside the temple. The ritual was in full swing.

The priest knew that Ek Chuah was smiling with delight as the foam began to spill over the edge of the tecomate. He knew that life-giving fertility itself emanated from this foam, not to mention the delightful contrast in textures and tastes it provided to the mystical libation.

The sacred beverage was used in many important rituals, and there was a feeling that if you missed one of them, your village or family might be destroyed tomorrow.

This particular ritual had everything to do with coming of age. The adolescent son of another priest was to ascend to adulthood tonight, so this ritual in particular had to be handled just right. He needed to be connected to the gods, especially to Ek Chuaj, the god of the sacred fruit of the cacao tree.

The priest drank deeply from the sacred beverage. His eyes rolled into the back of his head as he started to commune with the gods. A dramatic moment of silence and stillness entered the temple, as the priest received profound wisdom from the gods.

At last, it was the young man’s time to drink. He took the next sip of cacao, and in that instant, he felt as though he had one foot here on Earth, and one foot in the realm of the gods. He was a priest now, too.

Well, maybe something like this happened. We know that there were indeed many ancient rituals centered around cacao, the plant from which we get chocolate. Unfortunately, our understanding of the past is limited by what we can infer from primary sources and anthropological evidence.

That is to say, there’s not a whole lot written about the specifics of an ancient Olmec or Maya ritual where cacao was imbibed, so we can only guess the details.

Fortunately for us, there’s a great deal we do know about cacao (raw chocolate), and how it came to be. Today’s essay brings together a trifecta of writers from different walks of life but with a passion for chocolate, history, science, and the human elements that weave it all together.

Andrew Smith of Goatfury Writes covers the history segment. From there, we move on to the science of chocolate making, written by Michael Woudenberg of Polymathic Being.

Then, yours truly of The Cacao Muse, will bring the whole story together, with some actionable takeaways for chocolate lovers today of how to appreciate the craft and improve the sustainability of chocolate. Our intense passion for and deep knowledge of all things chocolate made this a natural fit for all three of us!

Part I: History

by Andrew Smith

Chocolate’s origins actually aren’t too far away from the Olmec or Maya ritual I opened with. Some 5,300 years ago, and quite possibly much earlier, humans started making chocolate.. The Maya-Chinchipe culture provides the first evidence of this in modern-day Ecuador, where they left behind cacao residue on pottery fragments.

Over time, the use of cacao spread northward through Central America and into the Mesoamerican regions where the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec civilizations later flourished. The Olmecs were the granddaddy culture of the region, but we don’t know very much about their relationship with cacao, other than that they certainly consumed it, probably in the form of a fermented beverage (more on that in Michael’s segment).

It’s with the ancient Maya that we really get a good taste of cacao culture.

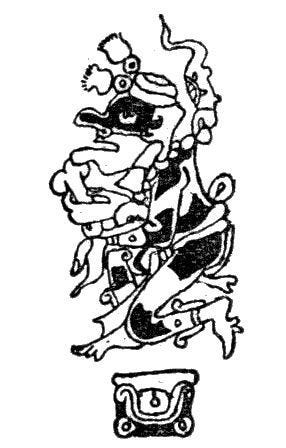

The Maya literally wrote chocolate (cacao, anyway) into their mythology. First, it was the “drink of the gods”, and it was used in important rituals—and as medicine. Far beyond this, though, the Maya actually had a specific god they called Ek Chuah, who was directly associated with cacao, among other things. Here’s a fantastic public domain image of Ek Chuah:

The Mayan version of chocolate was a spicy, frothy, and bitter beverage made from ground, roasted cacao beans, water, cornmeal, and chili peppers. If this sounds a bit more like a meal than a drink to you, that’s not really unusual for the ancient world, as we described in “An Ode to Beer.”

They also used cacao beans as currency. This implies that they had a meticulously calculated value, meaning a great deal of thought went into cacao beans and their cultivation, beyond even ritualistic ceremony or sustenance use.

The Aztecs, too, placed a premium on cacao beans, even though they didn’t grow their own—they imported them! And, in addition to the Mayan-style beverage, the Aztecs added their own twists with vanilla or honey.

The Spanish brought this incredibly important food across the ocean for the first time. It wasn’t a huge hit at first—remember, chocolate was a bitter, spicy drink, and Europeans were wildly in love with refined sugar by this time.

Thanks to a brutal slavery regime, sugar was already widely available across the European continent, so it was natural to combine sugar with chocolate. Someone added a little milk to the mixture, and suddenly a rich delicacy became widely recognized.

But a question remains, how did we go from a fermented drink, to a chocolatey bitter drink, to the smooth and delicious bars we now enjoy? That’s where Michael is going to take over and talk about the science of chocolate.

Part II: Science & Chemistry

The cocoa bean is where the delicious flavor and history originate and has a complex process to convert to the flavor we know. but unlike plain old vanilla which only grows on a specific orchid and requires the hand pollination of flowers that are open for less than a day…

Well, I guess plain old vanilla is pretty complex too, and interestingly the second most expensive spice in the world, but I digress.1

Cocoa, not to be confused with coca, grows in the Amazon Rainforest. The fruit we care about is contained in a cocoa pod that’s between 6 and 8 inches long with a thick rind holding in around 40 sweet, sticky, and white pulpy seeds that taste a bit like lemonade. Clearly, we are nowhere near that wonderful flavor of chocolate.

In fact, to get to the flavor we love, these beans are actually fermented for a week as the first step after harvest. This fermentation is not at all like what we explored in “An Ode to Beer” but it uses a similar chemical process to reduce the pulp and alter the flavor of the little beans ensconced in the pulpy flesh.

But wait… Chocolate is a fermented food? Well, that was the first drink those ancients made from it. That surgery pulp ferments just like any other fruit and makes an alcoholic liquid. It also leaves behind the little cocoa beans as a by-product and this is where the science gets interesting. Fermenting that initial pulpy, lemonade flavored material surrounding the bean does a whole complex series of things

First, natural yeasts and bacteria that are already present begin to ferment the sugars into alcohol. Which they originally drank but then discovered that the beans soak in the alcohol and absorb esters and floral-tasting fusel alcohols; read flavor. The ancients then found that if you didn’t drink the alcohol right away, after a couple days it is consumed by a bacteria to produce acetic acid.

Once again, the beans stew in a bath, this time acidic, which changes the chemical composition of the cocoa beans. This fermentation process adds flavors and then breaks down proteins into amino acids and complex carbohydrates into simple sugars giving us the complex chocolate flavors we expect.

Once the fermentation is complete, the beans are sun or oven-dried until their moisture is reduced down to 6%. This drying process helps separate the shells from the even smaller nibs on the inside in a step known as winnowing. At this point in time, the original pod, weighing almost a pound, is reduced to less than 2 ounces of cacao nibs!

But we aren’t done yet. The next step is roasting, which helps darken the beans’ color and finally solidifies that chocolate flavor we’ve been expecting. This is because the smaller compounds created during fermentation react with the roasting process and develop into chocolate’s unique flavor. At this point in the process, we have cocoa nibs like those you find in the store.

Now this is also where that first chocolate drink that the Europeans appropriated comes from. It’s bitter, a little spicy, and not at all what we think of as chocolate yet. This is where the Europeans took over production with their industrial capabilities and took chocolate to the next step.

Continuing the process, the nibs are then ground and sometimes treated to increase the pH in a process known as alkalization or Dutch Processing. This helps adjust the flavor and mouthfeel of the final chocolate. Regardless of whether we alkalize or not, the output is a paste called cocoa liquor which is then processed to separate cocoa butter and cocoa powder, both of which are required for further chocolate production.

Now we are finally at the step where we can start to make what we recognize as chocolate! We now blend the cocoa butter and powder back together with sugar and, heaven forbid, milk, to create a smooth chocolate in a process known as conching. This process develops the flavor and texture of chocolate, removes volatiles, and coats sugar crystals in delicious cocoa fats.

There’s one final step to ensure consistency and that’s called tempering where the paste is heated and cooled to create a crystallization process that allows the chocolate to shine, literally as well as snap, melt, and yet hold its form under room temperature.

Here’s a fun infographic if all this information made you a little lightheaded:

If you thought coffee beans had a lot of steps you were unaware of, cocoa takes it to the next level. Starting from a pulpy white lemonade-tasting fruit birthing the initial alcoholic beverage, transitioning through to roasted nibs to make the first chocolate drink, fusing with the European love of sugar and the introduction of mechanical processes, we end with thick, dark, and decadent chocolate.

Let’s turn it over to Birgitte to talk to us about the nuances of our relationship with a food that is both sacred and delightful, and the craft that fuses this science with cacao’s innate biology to create the vast array of chocolate delicacies we enjoy today.

Part III: A Sacred Craft

by Birgitte Rasine

We’ve all heard of superfoods. Açai berries, leafy greens, nuts, seaweed, mushrooms, and of course, chocolate. Whether or not a specific food is an actual “superfood,” nutritionally speaking, is a matter of debate, but there is a much deeper, more ancient and more fundamental meaning that defines our relationship with the things that keep us alive and make us thrive, and that is the sacredness of a food.

If we rewind history even just a touch, grocery stores, global supply chains, and strawberries in winter2 instantly evaporate, and we’re looking at millennia of largely manual, lightly mechanized agriculture, and ancient methodologies such as forest gardens and terraces. For people living off the land, as humanity has for most of our history, subjected to the whims of the gods (read: weather and natural ecosystems), a food packed with nutrition and flavor becomes much more than just breakfast or dinner. It is a sacred connection to Mother Earth, to the larger natural cycles that govern our world… in truth, a direct line to the gods that govern it all.

Cacao was one of those direct lines. It used to be sacred. So sacred it sparked creation myths. So sacred only kings, priests, and the nobility were allowed to partake of it. Today, it is a commercial product. A commodity. A financial instrument called a “cocoa future.” Worst perhaps of all, it is a driver of environmental degradation and forced labor generating obscene profits for Big Chocolate.

You might argue that like the Mesoamerican cultures, we also celebrate key moments in our lives—the coming-of-age of our children, our marriages and anniversaries—with chocolate. But the difference is that most of the chocolate we eat today has been processed nearly beyond recognition, and it’s not part of the ceremony any more. It’s sitting on the buffet table rather than in the sacred fire.

How did we get here? How did cacao lose its sacred mojo?

It was in part because other people started to tell cacao’s story—the Spanish at first, then the Europeans, and the rest of the world once it really got going. They started to change it. Add to it. Mix in different ingredients and viewpoints. At first, that wasn’t a bad thing. But over time, perhaps because there were more and more people disconnected from cacao’s origins and the land where it grows, and perhaps because the intention of the Conquista was to, well, conquer, the story turned into a tale of profit and greed.

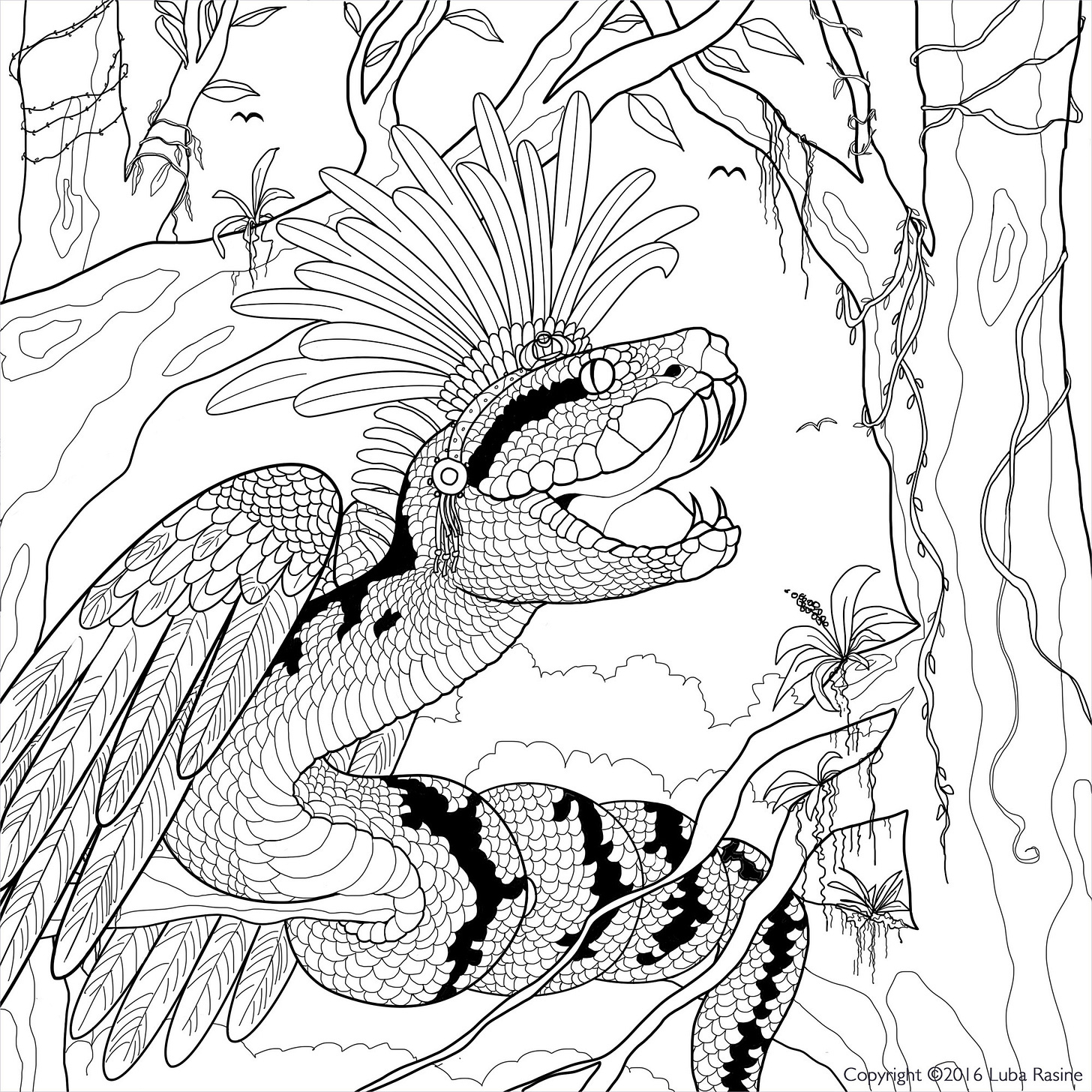

In one of the scenes in my novel The Jaguar and the Cacao Tree, the great Feathered Serpent winds her way around the trunk of the Sacred Cacao Tree, a double helix intertwining the energies of Life and Cacao. It’s a metaphor for the code of life that every living thing carries—a code that mutates and evolves, just like the myths and stories we carry down through generations. We’ve always had foundational stories of trees and serpents (ok maybe an apple here and there) to preserve and embody that code. For the Toltecs, it was the Feathered Serpent who brought cacao down from the heavens to the people. Curiously, in the cacao-producing regions of Mesoamerica, it was the Cacao Tree, not the Ceiba Tree, that was considered to be the sacred Tree of Life, the World Tree.

Could it be that somehow, subconsciously or intuitively, the ancient peoples of Mesoamerica sensed the intimate, powerful connection between their biology and that of cacao, whose DNA is more complex than that of humans? It’s true—theobroma cacao has 47 times more DNA per cell than we do. Not only that—we have 25,000 genes while cacao has 27,000. Indeed, any self-respecting Tree of Life should embody the full breadth of genetic variety across its species, no? Here, again, myth stumbles onto science, or perhaps vice versa: genetic diversity produces stronger resistance to disease and pests, thus rendering the plant in question seemingly invincible… protected by the gods. And, best of all for us hedonists, more diverse flavor profiles.

Enter the craft chocolate maker. This is the artisan who makes small batches, generally by hand in smaller facilities instead of large industrial factories. These are the masters who are deeply involved in every phase of the process of making chocolate, from selecting and roasting the beans to conching and tempering the resulting heady substance we call chocolate, and who focus intently, passionately, on flavor, craft, and quality. These are the people who are bringing us back to a sacred relationship with cacao and chocolate. Chocolate was always meant to be celebrated, respected, and honored, not roasted to death, muddied with chemical emulsifiers and preservatives, and choked with oils and sugars. Once you taste real chocolate, once your palate is set alight with flavors your brain won’t be able to express in words, all the commercial stuff will taste like cough syrup. Or cardboard dipped in mud.

And not a moment too soon. The past several decades have given us a conveyor belt of adulterated, industrialized chocolate that has bled cacao’s flavor profile dry and replaced it with plasticized sugar. Little wonder we are so keen on returning to our culinary roots… and even less wonder when you realize we are, in fact, living through a craft food renaissance. Japanese Kobe beef. Artisan cheese. Specialty oils and vinegars. Liquid death water in a can.3 Craft beer. Craft coffee.

Craft chocolate still has a long way to go compared to coffee and beer, dollars wise. The global craft beer market reached US$130.4 billion in 2023, according to the IMARC Group. The global specialty coffee market was estimated at US$21.9 billion in 2022, according to Research and Markets. Coming in third is craft chocolate, valued at $13.3 billion in 2023, according to Cognitive Market Research.

The exact number of craft chocolate makers is not easy to find, due largely to natural variability in the market (given how complex chocolate making is and how tough it is to survive as a small business to begin with), but according to Carla Martin, a source I would personally trust, there are currently 480 makers worldwide, of which nearly 200 are located in the United States. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, this means the U.S. is the heart of the global craft chocolate movement. Apologies to Belgium and Switzerland! I can personally attest to the extraordinary diversity, skill, dedication, and mastery of the chocolate makers in this country. I’m a chocolate judge—I should (and do) know. We might not do politics, healthcare, and education too well, but damn we make some fine craft chocolate.

There is no way I could possibly list, here, all of the wonderful chocolate makers I have had the pleasure to get to know, and whose chocolate I have been blessed to taste. It is, admittedly, a perennial problem. But that is precisely why I produced a 25-day Holiday Tour last December—consider it a preview of just 25 of the world’s best artisan chocolate makers, at least according to my humble opinion. 😎

Must all good things come to an end? Perhaps only this essay…

So what is cacao telling us through its genetic code and through our mad passion for it? It’s telling us it’s one of our most ancient biocompatible plants. It is as genetically and biologically rich as we are, if not more so. It delivers to us all that we need to live in health, joy, and harmony on all of the primary levels of our culture and civilization. It blends and infuses into us, just as we nurture and transform it. Cacao and humanity are that golden double helix—inseparable, inevitable, in love.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this “Ode to Chocolate,” learned a little, and perhaps even discovered a few new chocolate makers to try.

May the chocolate you partake of henceforth, be of the real and genuine kind, may your palate open up to a new universe of flavor and texture, and may you never have to repeat your life B.C.C.—Before Craft Chocolate.

And if you have a favorite chocolate to share, a chocolate story to tell, or a burning chocolate question to ask—which, of course you do—Michael, Andrew, and I want to hear about it in the comments!

Fun fact, vanilla is also Mesoamerican and the Aztecs, after conquering much of Central America would mix vanilla with cocoa into a drink called “xocolatl,” which later inspired modern hot chocolate. Coincidentally, cocoa and vanilla were mixed together for much of its early history in Europe before splitting into two unique flavor groups much later on.

We refer, of course, to the Northern Hemisphere.

Not really a food, but I just had to add it. Ya gotta admit they have killer branding.

Birgitte, thank you for hosting this, and for making sure it came together really well! Folks, all three of us enjoyed geeking out together.

So funny aside, that silly Three Amigos Gif that Andrew put in motivated me to watch the movie for the first time (I know, I know). Now my youngest kid keeps singing 'My little buttercup' and quoting the movie!! 🤣